When I was first getting started, I assumed technical content failed for fairly obvious reasons. Either the underlying technology wasn’t very good, or the explanation itself was wrong. Bad assumptions, incorrect diagrams, missing steps (classic technical failures).

I was lucky enough in my early roles to be learning from incredibly talented technical storytellers, who taught me to recognize the more common failure mode: the explanation is technically correct, carefully reviewed, and still ineffective. Not because it’s inaccurate, but because the reader never quite makes it far enough (or deep enough) to understand what’s actually being said.

(Let’s be clear, that’s really only part of the problem, but we’ll talk about making content discoverable in the first place some other time!)

I’ve seen engineers invest weeks in new guides that get skimmed once and ignored. I’ve watched sales processes stall because the people responsible for signing the check never fully understood what problem was being solved. And I’ve seen well-meaning “storytelling” advice make things worse by encouraging metaphors that feel friendly but collapse under even mild scrutiny.

What all of these situations share isn’t a lack of intelligence or effort. It’s a breakdown in translation.

That breakdown lives in the space between engineering and narrative. Not storytelling as embellishment or persuasion theater. Storytelling as a way of helping real people understand complex technical work well enough to make decisions, take action, and move forward without sacrificing technical truth along the way.

What is technical storytelling

Technical storytelling is the practice of framing technical work so that its logic, constraints, and implications are understandable to someone who isn’t already embedded in the system.

That framing is often mistaken for simplification. In reality, it’s closer to exposure. Most technical systems already contain a narrative structure: a problem that prompted the work, constraints that shaped the design, tradeoffs that ruled out other approaches, and outcomes the system is meant to enable. Engineers tend to internalize that story as they build. Everyone else encounters only the artifacts.

I saw this repeatedly when I was working on developer marketing at Okta. Developers don’t usually misunderstand the core problem OAuth solves—they grok why delegated authorization exists. What they don’t understand is what OAuth, and ultimately Okta, is doing on their behalf once they hand control over. Most explanations leap straight into flows, scopes, and redirects, which are accurate but skip the part developers actually care about: whether this abstraction is something they could, or should, build themselves. Developers are rightly suspicious of systems they can’t reason out. When you explain OAuth in terms of what’s happening behind the scenes, including how to wire it up, the abstraction becomes trustworthy instead of opaque. At Okta we often went one step further and wrote technical guides on how to implement OAuth both with and WITHOUT Okta.

I get it thought, the term “storytelling” starts to make engineers uncomfortable. It gets associated with distortion or gloss. Engineers are trained to remove ambiguity, not introduce it. Precision is the point.

But accuracy without context doesn’t guarantee understanding. A system can be described with perfect precision and still fail to land if the reader can’t see why decisions were made, how components relate, or what changes as a result. When that happens, the explanation isn’t wrong. It’s inert.

Good technical storytelling doesn’t make systems feel simpler than they are. It makes them feel navigable. The reader may still recognize the complexity, but they know where they are inside it and why it exists.

Why technical storytelling matters for technical teams

The impact of technical storytelling has very little to do with writing polish and a great deal to do with leverage.

When technical work is understood, it moves more easily through an organization. It encounters less friction, fewer misunderstandings, and less resistance rooted in uncertainty. It’s evaluated on its merits rather than on how well it was summarized in a single meeting or slide deck.

This becomes especially clear at the boundary between builders and decision-makers. In identity systems, for example, engineers naturally talk about threat models, token lifetimes, and protocol compliance. The people approving those systems are often thinking about breach risk, time-to-market, and long-term support burden. Both perspectives are valid. Without a story that connects them, they talk past each other.

Technical storytelling doesn’t remove that complexity. It reorders it. It allows engineers to explain why the constraints exist, and allows stakeholders to understand what those constraints protect or enable. When that translation happens, conversations get sharper, not softer.

The same pattern shows up in documentation. Most documentation technically answers the question it sets out to answer. The problem is that it often fails to answer the next questions (the ones that determines whether the reader does anything with the information at all). What is this for? When should I use it? What happens if I don’t?

Stories answer those questions naturally because they establish continuity. They explain not just how something works, but where it fits. Without that context, even good documentation feels like a set of disconnected pages rather than a path forward.

Know your technical audience before you write

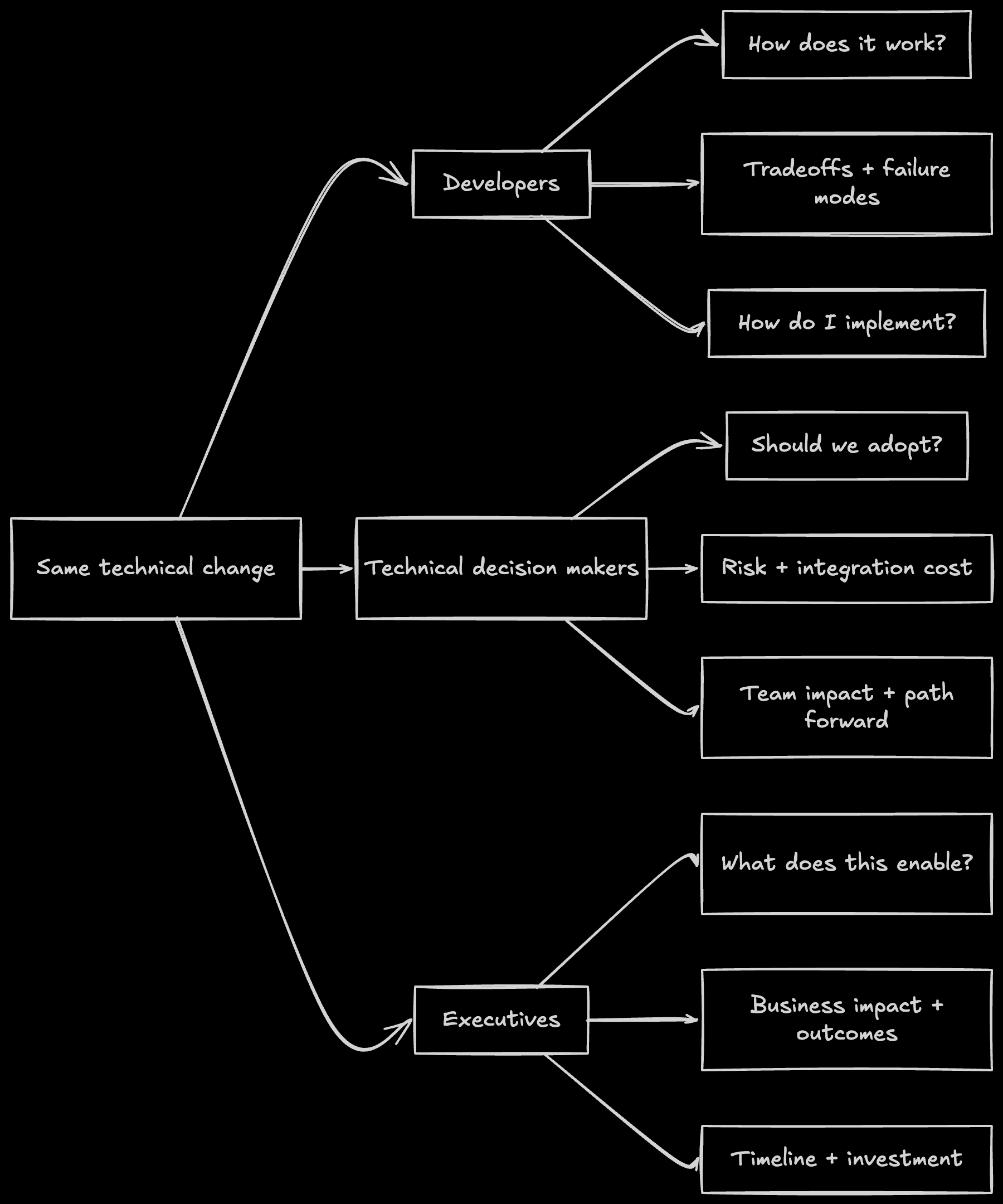

One of the fastest ways to undermine technical content is to treat “technical audience” as a single category.

Developers and builders tend to care deeply about correctness, depth, and respect for their time. They don’t need everything explained, but they do need the logic to hold. Oversimplification reads as condescension. Vague claims read as dishonesty.

I saw this clearly while working on feature flagging at Split. Feature flags are often explained as simple toggles, which is true in the narrowest sense and misleading in practice. Developers care about SDK behavior, evaluation latency, and failure modes. Technical decision-makers care about blast radius, rollback speed, and experimentation discipline. The same system needs to be explained differently depending on which decision the reader is trying to make.

This is why effective developer-facing content feels more like dialogue than delivery. When content anticipates real questions and responds to them directly, it builds trust and momentum. I’ve written more about this dynamic in Good Developer Content Is a Conversation, Not a Broadcast.

Executives and non-technical stakeholders are usually focused elsewhere entirely. They care about what the technology enables: speed, resilience, differentiation, efficiency. The mechanics themselves are secondary. The challenge is connecting those outcomes to the real constraints of the system without misrepresenting the work underneath.

A common mistake is writing a single explanation and hoping it somehow satisfies all three groups. It rarely does. Effective technical storytelling doesn’t dilute the work; it reframes it based on what the reader needs in order to decide.

Core principles that make technical storytelling work

Over time, I’ve noticed that technical stories that land tend to share a few underlying characteristics, even when they look very different on the surface.

Clarity consistently beats cleverness. Metaphors can help, but only when they map cleanly to reality. In developer marketing, I’ve seen OAuth compared to valet keys, feature flags compared to light switches, and secure tunnels described as “magic.” These metaphors work right up until the moment someone asks a real question (about scope boundaries, evaluation logic, or security implications). When the metaphor breaks, trust breaks with it.

Brevity matters, but not at the expense of rigor. Being concise doesn’t mean removing nuance; it means knowing which details are load-bearing and which are ornamental. Cutting the wrong thing doesn’t make content clearer. It makes it misleading.

The strongest technical stories balance evidence with stakes. Data establishes credibility, but stakes create momentum. Readers need to understand what changes if something works, and what breaks if it doesn’t. Without that context, even solid reasoning can feel academic.

Underlying all of this is a quiet but persistent question: so what? Every technical detail needs a reason to exist. If it doesn’t change a decision, enable an action, or alter an outcome the reader cares about, it needs to be reframed or removed.

How to structure a technical story for clarity and impact

When I sit down to brief or write technical content, I almost never start with the solution.

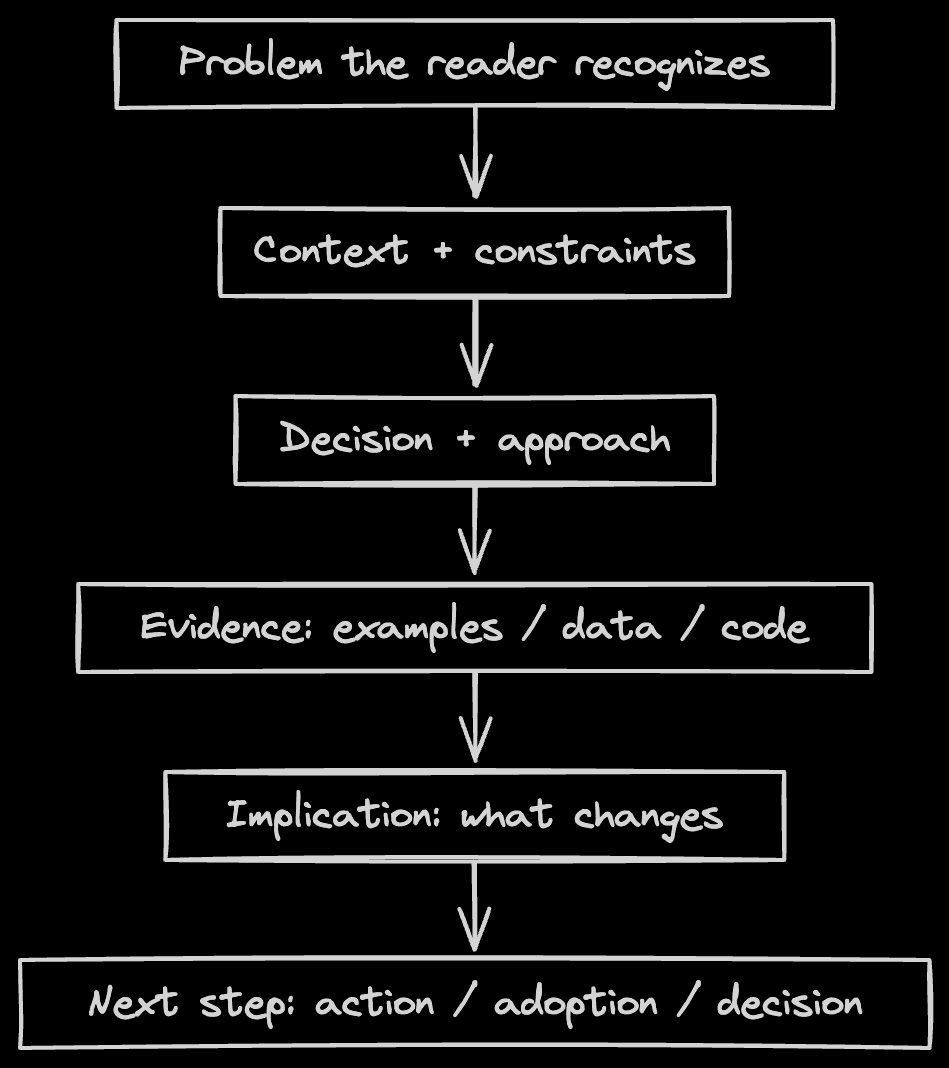

I start with the problem (not the abstract version, but the one the reader recognizes from their own experience). The friction they’ve already felt. The thing they’re quietly hoping someone will explain clearly.

From there, I establish context quickly. Why this problem exists. Why it hasn’t been solved already. What constraints shape the space. Without that grounding, the solution has nowhere to land.

Only once that ground is set does the technical approach begin to make sense. And when it’s introduced, evidence matters more than enthusiasm. Concrete scenarios, real examples, diagrams or code when they add clarity rather than decoration.

A technical story should also close deliberately. The reader shouldn’t reach the end wondering what to do with the information. Whether the outcome is a decision, an action, or a shift in understanding, the implication should be clear.

Techniques for better technical storytelling

Some techniques consistently help technical stories do their job more effectively, especially when complexity is unavoidable.

Leading with what matters to the reader is one of the most important. I saw this often with ngrok. Many explanations start with tunnel mechanics and network plumbing. What developers usually want to know first is much simpler: how to test a webhook locally, how to share a local service without deploying, how to stop fighting their firewall for the afternoon. Starting there doesn’t hide the underlying complexity. It earns the right to introduce it.

Cutting jargon without cutting accuracy also matters. Jargon can be useful shorthand among peers, but it quickly becomes a barrier when the audience shifts. Defining terms when they matter (and replacing them when they don’t) keeps explanations precise without becoming exclusionary.

Concrete examples do more work than abstractions, but only when they’re chosen carefully. A misleading example can create false confidence that’s harder to undo than confusion.

Finally, showing the human side of the work helps anchor understanding. Technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It’s built by people, used by people, and constrained by real-world conditions. Acknowledging that reality makes technical content feel grounded rather than theoretical.

Technical storytelling mistakes that kill credibility

Many of the most damaging mistakes in technical storytelling come from good intentions.

Let’s state the obvious: oversimplifying until the explanation becomes technically wrong is the fastest way to lose trust with a technical audience. Once accuracy slips, nothing else matters.

Also, burying the point under layers of implementation detail makes it impossible for non-builders to engage. If someone has to understand your entire architecture before they know why it exists, you’ve already lost them.

This can be where a lot of developer marketing quietly fails. Content that’s written to sound technical (dense with buzzwords, feature lists, and architectural name-dropping) gives developers nothing they can actually use. This failure mode becomes especially visible when AI is involved — fluency without accountability produces exactly this hollow content. I’ve written about responsible AI content creation and how to avoid it. When content doesn’t help someone ship, debug, or decide, it gets ignored.

Forgetting to answer “so what” leaves readers stranded. They may understand how the system works, but not why it matters or what to do with that understanding.

Writing primarily for yourself (or for people exactly like you) assumes a shared context that often isn’t there. The curse of knowledge is real, and counteracting it requires deliberate effort.

How to measure technical storytelling effectiveness

One of the advantages of technical storytelling is that it’s measurable in ways most communication advice isn’t.

You can see it in whether readers finish the content. In the quality and quantity of follow-up questions. In how quickly teams adopt or align around a decision. In feedback that engages with substance rather than surface confusion.

The most reliable signal is simple: did people understand enough to act?

If they did, the story worked.

Technical storytelling is a strategic advantage

I’ve come to think of technical storytelling less as a writing skill and more as a form of respect (respect for the reader’s time, for the work’s complexity, and for the decisions that understanding enables).

Teams that tell technical stories well don’t just explain their technology more clearly. They shape how it’s perceived, adopted, and valued. They make emerging systems make sense to the people building with them.

This connection between understanding audiences and driving adoption is at the core of developer marketing itself, something I’ve explored more deeply in What Is Developer Marketing? A Guide from the Trenches (2025).

That’s not a nice-to-have. It’s a strategic advantage.

FAQs about technical storytelling

Technical writing focuses on accuracy and completeness. Technical storytelling adds structure and context so that information becomes understandable, memorable, and actionable.

Technical storytelling can absolutely work for highly specialized topics. In fact, the more specialized the work, the more important it becomes for making that work legible to adjacent audiences.

You don’t need to be the subject matter expert to tell a technical story, but you do need to partner closely with those who are. Asking “why does this matter?” repeatedly and focusing on translation rather than performance is where the value lies.

Technical storytelling works across formats (documentation, blog posts, presentations, demos, videos). The medium changes, but the principles don’t.

A technical story should be as long as it needs to be to deliver understanding, and not a word longer.